How to keep confidence in the gaze?

Pia Cordero

Rushes (1986), Alfredo Jaar, images courtesy of the artist

Alfredo Jaar's visual projects face us with the social and political current state, anticipating already in the 1980s the limitations and conditioning of our gaze in a time where images were becoming more ephemeral. Regarding the relationship with the media before the Internet, the artist points out the following:

Information became a key aspect of my life from the beginning. That is why I started subscribing to many magazines and newspapers, from around the world, because of this passion, this obsession with information. (..) Whiteout knowing, I was very early on, in the late 70s, starting to use a methodology that would become a key methodology in my work: basically to inform myself, to research – again, this is pre-internet¬ and then to act upon this information .1

Exploring the artist's visual projects offers us certain elements to understand our relationship with informative images in a time characterized by the decline of communication. Jaar's critical positioning, that is, the strategies of visual production characterized by the control of the acoustic and lighting conditions of the exhibition space, the use of written texts and the concealment of images, allow us to connect with the works through exercises of recollection, many of them intellectual, but also affective and emotional.

In the exhibition catalogue, The Lamentation of Images (1999), Debra Bricker, the exhibition's curator, stated that before travelling to Rwanda, Jaar had already been thinking about the effectiveness of the photographic medium and images. According to Bricker, the questions that began to arise in his projects of the 80s were: "How to elicit an emotional response from a viewer in a culture inured to widespread imagery of violence and cruelty? How to represent tragedy without exploitation? How to counter and transform the now conventionalized scenes of brutality promulgated by the mass media? How to adequately convey the enormity and weight of the injustice of mass killing?".2

Jaar's visual production strategies, which were made up in works before The Rwanda Project (1994-2000), can be brought together in what we could call a "model of visual information criticism" insofar as they explore the possibilities of representation of the photographic medium and our relationship with what is reproduced by images; for example, installations with fragments of documentary images on boxes, illuminated from the inside with fluorescent tubes and placed away from normal vision, which instigate the spectator to practice different visual and bodily approaches.Let us review Rushes (1986), Geography = War (1990), The Rwanda Project (1994-2000) and The Geometry of Consciousness (2010), Jaar's iconic works in which there is a direct inquiring into the idea of "certainty" connected to the photographic medium.

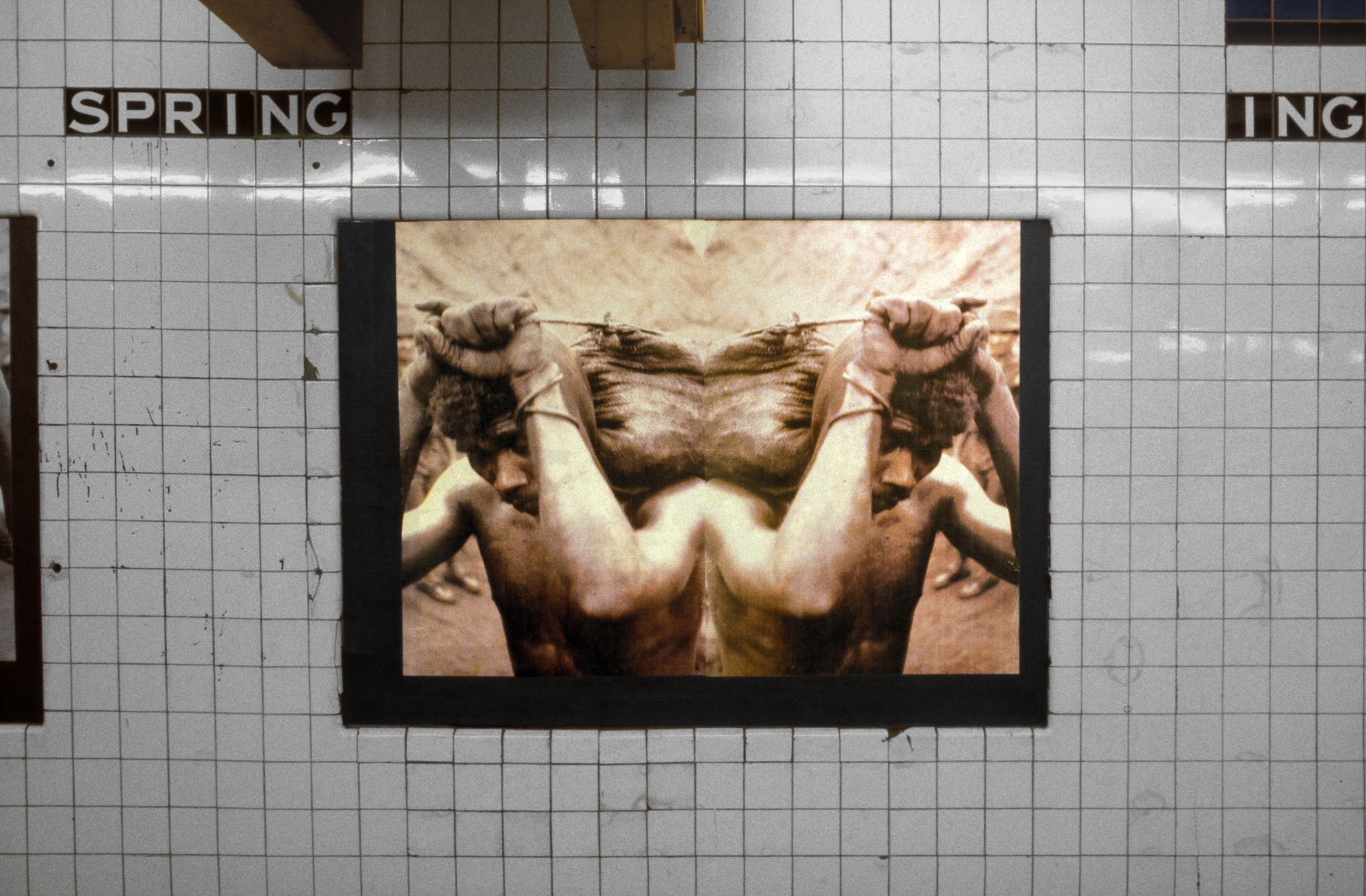

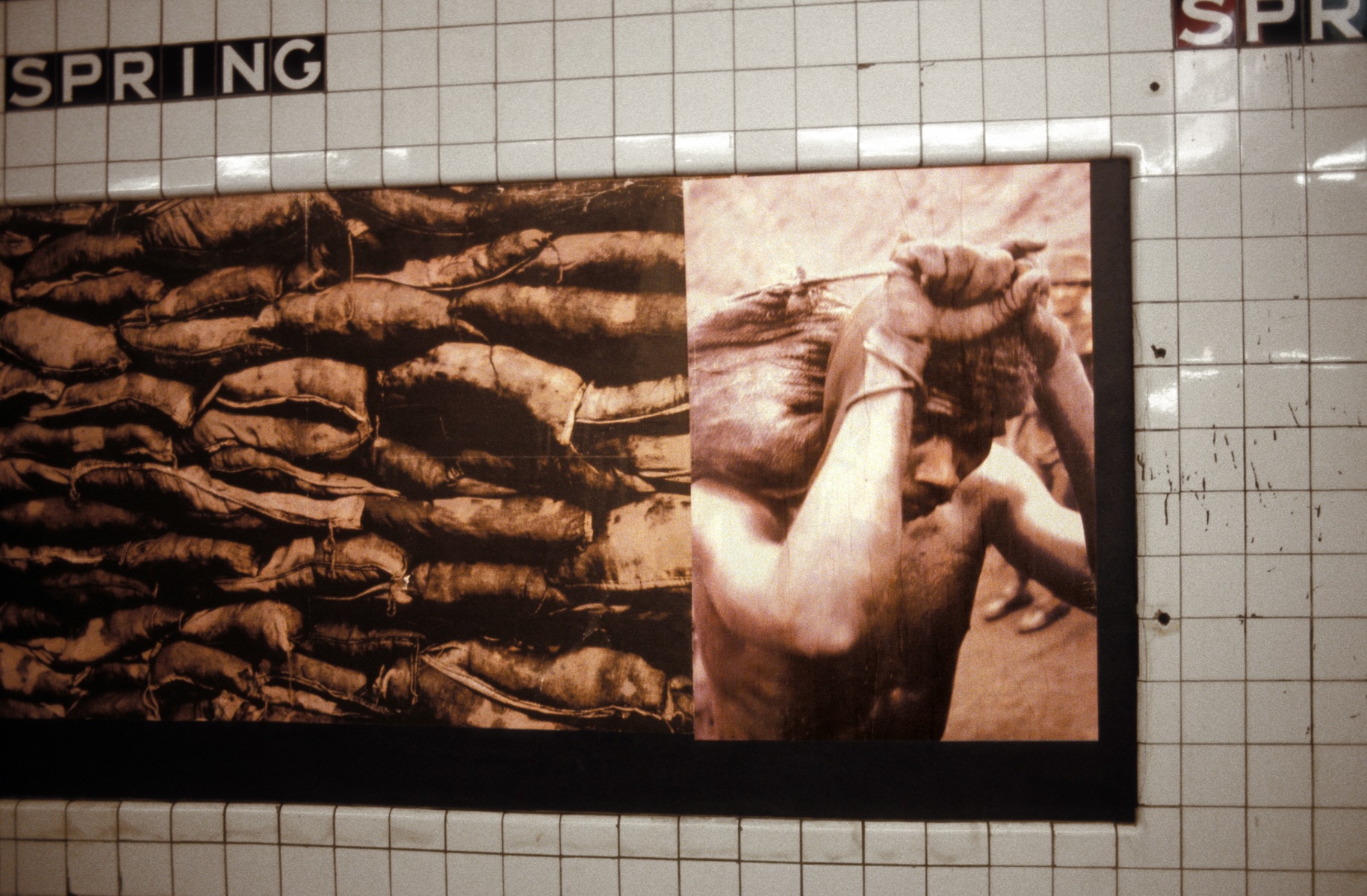

Rushes (1986)

It is a public intervention that Jaar carried out at the Spring Street subway station in New York City. A subway station heading towards Wall Street, where the artist displayed 81 photographs he had taken at the Serra Pelada gold mine in northern Brazil. The artist travelled to Brazil and documented the miners' work in situ, obtaining more than 1,200 photographs and 10 hours of video footage that showed the ecological disaster and precarious working conditions. Using the scale of advertising images usually found in subway stations, large photos of the miners' faces and bodies captured passengers' attention, often found inside the carriages, since some of the trains did not stop at the station.

Rushes (1986), Alfredo Jaar, imágenes cortesía del artista

Those who watched the images at the speed of the train witnessed a kind of cinematography script, made up of fragmented and discontinuous arrangements of photographs. These images reproduced the bodies of miners alongside the price of gold on several world markets. Jaar's moving images produced short circuits, destabilizing the conventions of the gaze of passengers accustomed to advertising images that mitigate the ability to observe. This is why the cinematographic language used in Rushes (1986) engages us with the question of the semantic autonomy of the image since there is no image truth that is independent of the image's context.

Geography = War (1990)

A large, sombre-looking installation, first exhibited at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, featuring photographic images reflected on the surfaces of metal barrels filled with water. The photographs were taken by Jaar in Koko, a town in southern Nigeria that had been turned into a dumping ground for toxic waste from Europe. Geography = War is emblematic because, as Jeff Derksen and Neil Smith suggest about the installation, as well as about Jaar's projects in general, it "caught the emerging neo-liberal moment in its ascendancy."3 Making geographical borders visible again is the same as making visible again the power that controls time and space, the same power that propagated the chimaera in the late 1980s that borders had dissolved through globalization.4

Geography = War (1991), Alfredo Jaar, images courtesy of the artist

The Rwanda Project (1994-2000)

In 1994, Jaar, who had been living in the United States since 1981, traveled to Rwanda weeks after the Tutsi genocide. A plane transported him and his assistant Carlos Vásquez to Kigali, the epicentre of the genocide in which one million people were killed. But was it enough to travel with a camera to the site of the wound where thousands of bodies were piled up and rotting in front of the helplessness of the survivors? Faced with the tragedy of the Tutsi genocide, Jaar realized that the camera was only a mediator between reality and the viewer. The artist then confirmed his intuition, namely that images alone are insufficient to produce a response. The photographic image is itself a new reality that implies, as the artist expresses, a gap between the experience of the fact and its photographic capture. For this reason, in the 25 works that comprise The Rwanda Project (1994-2000), Jaar has shown only six images of the 3,000 he made in Rwanda, noting:

I discovered that the images I had taken were completely inadequate –and, ironically, I had gone there myself in response to the inadequacy of the images in the media, which had not provoked any international reaction from politicians or from people.5

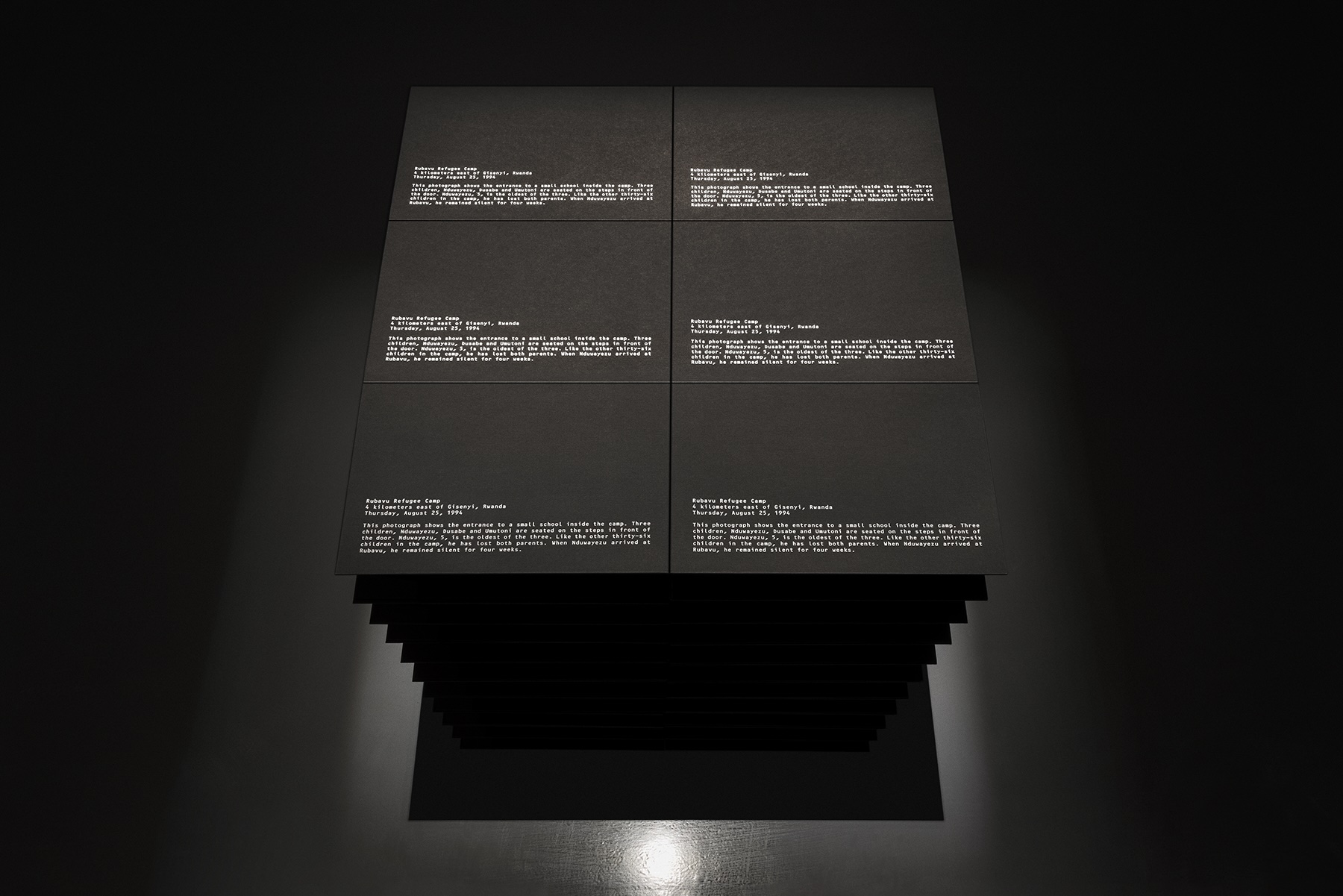

Real Pictures (1995) is one of the first works of The Rwanda Project, composed of a set of modular black boxes for photographic archives, each containing more than 550 photographs of Rwanda. The linear arrangement of the archive boxes, as well as the darkness of the exhibition space, made the installation function as a memorial. Each of the boxes had texts written on its surface with the names of people, places and events related to the Rwandan genocide. In Real Pictures, Jaar applied the inverse logic, hiding the photographs inside the boxes to make them visible. Referring to this operation, the artist observed:

If the media and their images fill us with an illusion of presence, which later leaves us with a sense of absence, why not try the opposite? That is, offer an absence that could perhaps provoke a presence6

Jaar's subtraction of images is, as Jacques Rancière mentions in his reflections on The Rwanda Project, a solution to the visual insensitivity caused by our voyeuristic way of relating to images. Rancière, reflecting on the artist's visual projects that explore our relationship with visual information, proposes: “Images blind us, it is said today. It is not that they conceal the truth, but that they trivialize it.”7

Of the 3,000 photographs Jaar took in Rwanda, he has only shown five or six, given the problem of ephemeral using images in an era characterised by essentially visual culture and, therefore, insensitive to the experience of pain. Within The Rwanda Project, The Eyes of Gutete Emerita (1996) stands out. The first version of the installation were located in two somber spaces. In the first, the spectator had to slowly walk along an 8-meter stretch to read the story of Gutete Emerita, a young Rwandan woman whom Jaar had met in the church of Ntarama and who had witnessed the murder of her family by the Hutus. The artist narrated his encounter with the woman in the first person through three texts. The first one read::

Gutete Emerita, 30 years old, was attending mass with her family when the massacre began. Killed with machetes in front of her eyes were her husband Tito Kahinamura, 40, and her two sons, Muhoza, 10, and Matirigari, 7. Somehow, Gutete managed to escape with her daughter Marie-Luoise Unumararunga, 12. They hid in a nearby swamp for three weeks, coming out only at night in search of food.8

The second text read as follows:

Gutete has returned to the church in the woods because she has nowhere else to go. When she speaks about her lost family, she gestures to corpses on the ground, rotting in the Africa sun.9

Finally, the third text read:

I remember her eyes. The eyes of Gutete Emerita.10

After reading the texts, the spectator entered an adjacent room, where there was a large light table (600 cm x 600 cm) with a million slides reproducing the eyes of Gutete Emerita, which functioned as a metaphor for the million dead in the mass grave in Rwanda. Next to the slides were magnifying lenses that allowed the spectator to gaze at the woman's eyes from 1 centimetre away. About the search for proximity between the eyes of the spectator and those of Gutete Emerita, Jaar points out the following:

I am suggesting here that her eyes acted as a camera who saw something that we could not see. The question here is: How do we bridge the gap between our eyes and her eyes11

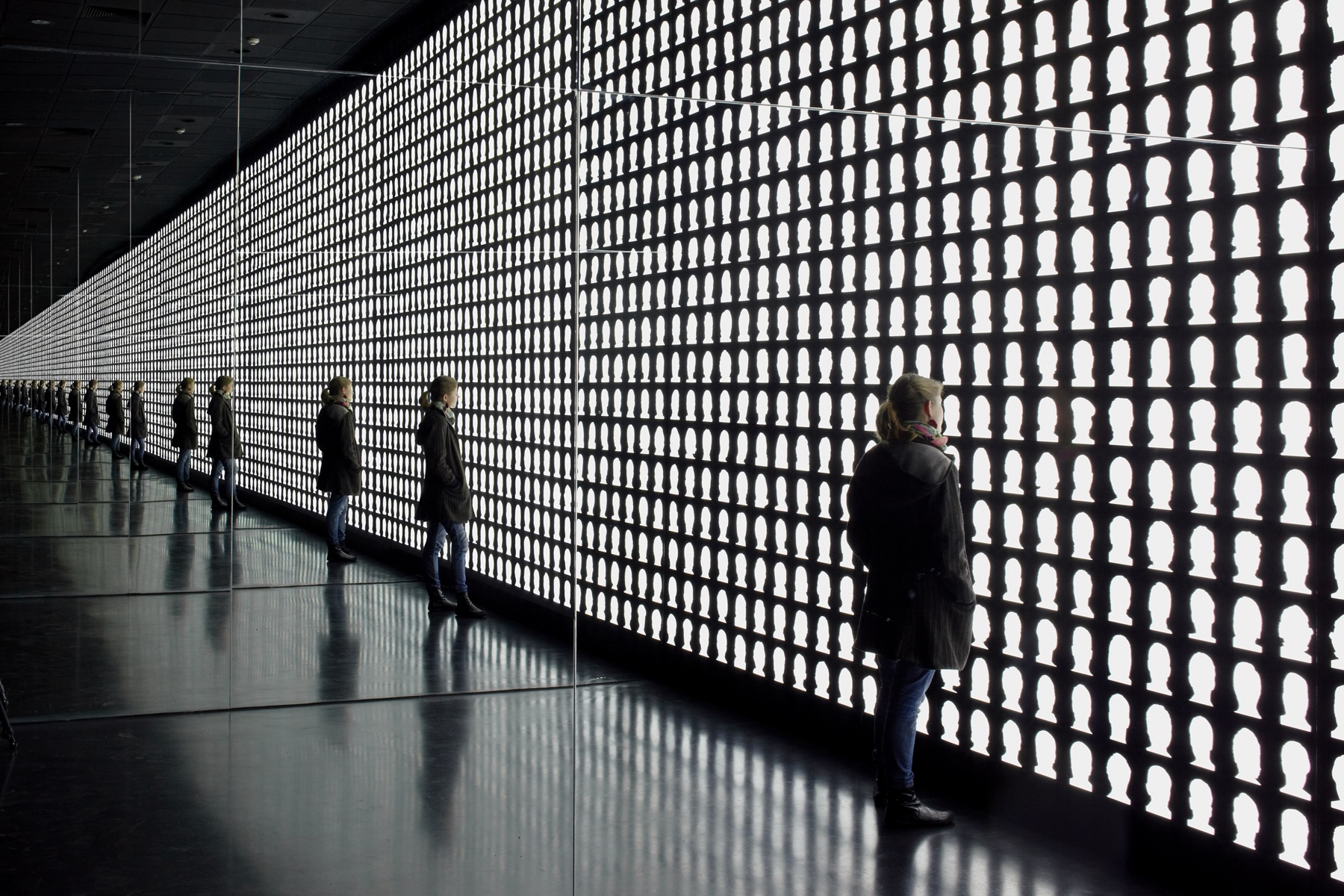

The Geometry of Consciousness (2010)

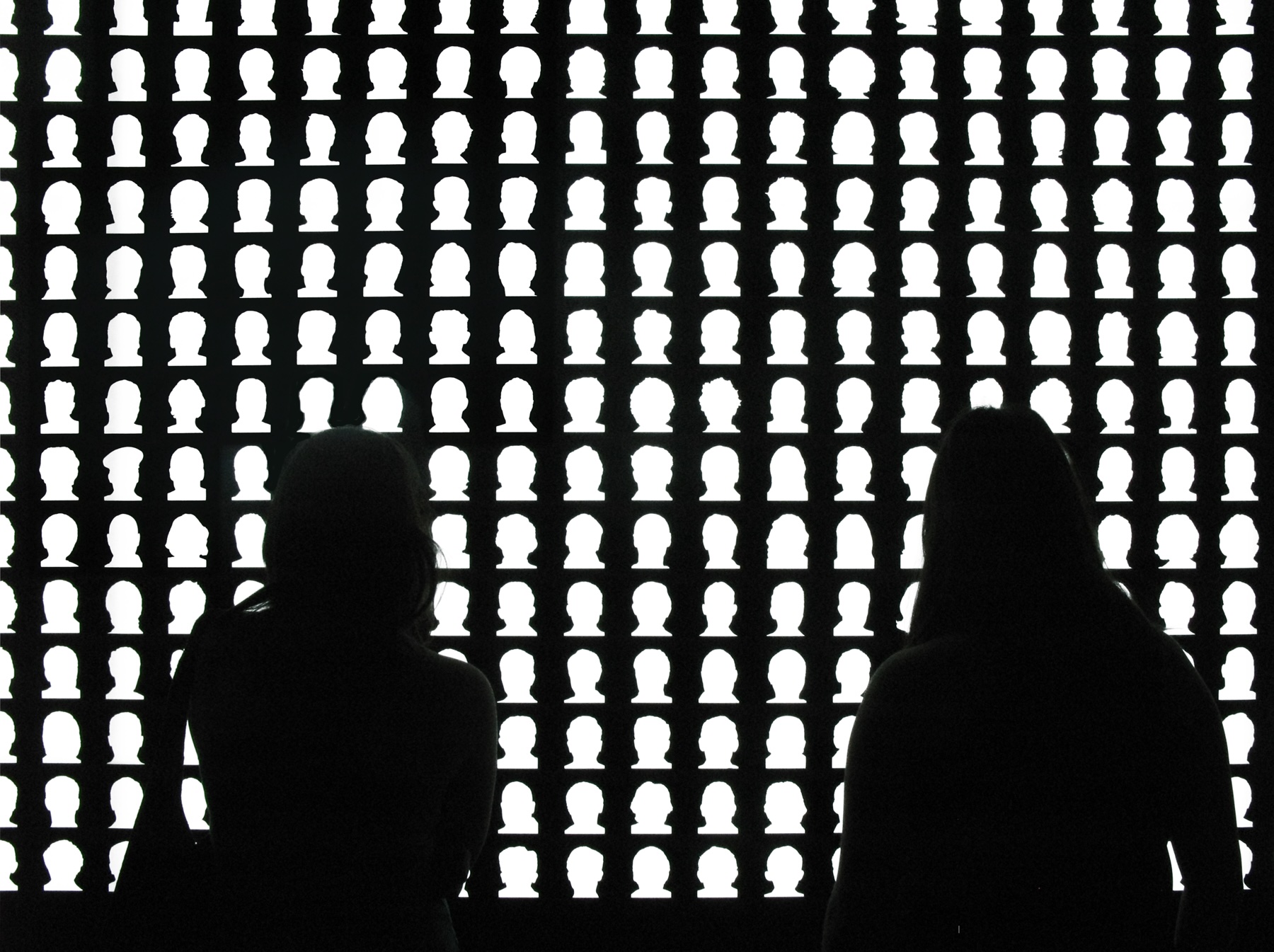

Through work with fragments of photographs from the 1980s until their total concealment in The Rwanda Project, Jaar seeks to involve us critically and emotionally with reality. This search extends to The Geometry of Consciousness (2020) and can be explored from the perspective of the artist's visual strategies, referring to the model of criticism of visual information. The installation is Jaar's first, and so far only, large-scale public work in Chile and consists of an intervention in the structure of the Museum of Memory and Human Rights (MMDH). The work is located on the basement level of the museum. A staircase leads visitors from the building's esplanade to a small, dark room. Once inside, visitors are immersed in complete silence and darkness for 2 minutes, until the space is illuminated by one of the walls covered with 500 white silhouettes. These silhouettes depict people chosen by the artist and those who disappeared during Pinochet's military dictatorship. The walls adjacent to the silhouettes are completely covered with mirrors, creating an optical illusion of infinite duplication.

The geometry of consciousness positions us as "point zero," from which our lived experiences, both reminiscent and creative, constitute its meaning. We can define these experiences as antifictional experiences. The expression “antifiction” was introduced by Philippe Lejeune to refer to stories that develop under the pallium of sincerity, renouncing invention.12 An antifictional experience will then describe what is lived from the commitment to the truth of the events. The immediacy of recollection and creation seems to enable a reunion with ourselves when we detach ourselves, even for 3 minutes, from the guidelines that lead and dominate our lives.

Notes

1. Alfredo Jaar, "I need to understand the world before acting in the world," Tonight no poetry will serve = Kun runous ei riitä (Findland: Nykytaiteen Museo 2014) 69.

2. Debra Bricker Balken,Alfredo Jaar. Lament of the Images (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT List Visual Arts Center, 1999), 13.

3. Jeff Derksen, Neil Smith, "A geography of the difficult," Alfredo Jaar (Roma: Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Roma 2005) 59.

4. Geographers Jeff Derksen and Neil Smith propose that Jaar's visual projects over the past 25 years unfold through three creative movements: "the malleable geography of capitalism and anticapitalism; the cultural politics opened after conceptualism and the expansion of the art object into the public sphere; and the projections of culture and especially art production as both body and anti-body of a highly uneven globalization." (Derksen y Smith, Ibid., 55).

5. Jaar Ibid., 70.

6. Jaar,"Telesymposia. Representations of Violence. The Limits of Representation," Trans>arts.cultures.media,3/4, 1997, 58.

7. Jacques Rancière, "El teatro de las imágenes," El lamento de las imágenes (Chile: Ediciones Metales Pesados 2008) 69.

8. Alfredo Jaar, "Lecture," La citta degli interventi: la generazione delle immagini III (Milano: Comune di Milano 1997) 180.

9. Jaar, Ibid.

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

12. Philippe Lejeune, Autogenèses. Les brouillons de soi 2, Tome 2 (Paris: Seuil, 2013).