Alfredo Jaar: A Witness to His Time. Early Works (1974-1981)

Elisa Cárdenas Ortega

Images: Jorge Brantmayer

All history is contemporary history

Benedetto Croce

Visitors to the Museum of Memory and Human Rights in Santiago de Chile will encounter an artistic installation in an underground structure, the observation of which requires a certain time, in a narrative record that displays, as a final and resounding image, 500 silhouettes of faces that are lost in infinity. The work The Geometry of Consciousness evokes the well-known image carried by the relatives of detained-disappeared and their heart-wrenching question: Where are they? It was created by Chilean artist Alfredo Jaar (1956) as a permanent installation for the Museum of Memory in 2010 when President Michelle Bachelet inaugurated it.

Alfredo Jaar is the 2013 National Arts Award winner and one of the most important Chileans in the world in contemporary art. A resident of New York since 1982, he can be classified as a conceptual art movement, although he prefers to define himself as "can architect making art" referring to his original profession, which he developed at the University of Chile before emigrating. Alfredo Jaar uses media such as photography, sculptural and light installations, sound, videos and interventions in public spaces to exhibit his aesthetic discourse facing situations arising from the use and misuse of power and the social crises that these actions often provoke. His works on Africa are well-known; they point out the question of how a continent rich in resources lives in critical situations of poverty and misery due to macro-structures of exploitation. In his works, he has shown immigrants from Europe and Asia, refugees, prisoners, HIV victims, the undocumented, marginalized intellectuals, likewise artists, writers and thinkers women, who have been undervalued and the unemployed.

His The Geometry of Consciousness was the corollary of a slow return of his work to the national scene after decades - apparently - very far away, not only in kilometres but also due to the absence of the image and the idea of Chile in his production. But in all the years since his departure to the United States, Alfredo Jaar has followed the news and events in Chile very closely. Information is, indeed, the core of his artistic production, as he with critical distance reviews and analyzes the press and media; he uses the world’s diversity of realities as a main support for his work. As the canvas is for a painter or the body is for a performance artist, Alfredo Jaar conceives his work on and from the world's map and context.

Until not many years ago, it was unknown that Jaar began as an artist with incipient works, budding exercises of a young architecture student most of whom referred to the coup d'état and the beginnings of the civil-military dictatorship in Chile. These small works were kept as sketches and projects until international curators convinced Jaar to bring them to light as part of his retrospective exhibition in Berlin in 2012. These small works were kept as sketches and projects until international curators convinced Jaar to bring them to light in his retrospective exhibition in Berlin in 2012. Since then, these early works on the crisis in Chile beginning in 1973 have been rescued and partially exhibited in different international spaces; they were the main element of an exhibition between September 2023 and March 2024 at the National Museum of Fine Arts, in Santiago de Chile, one of the most important cultural activities in the framework of the commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the coup d'état in this country.

These series are made up of some 70 works that bear witness to what happened in Chile. They are pieces made in the first years - the most complex years of the dictatorship - that reflect the social climate of the time from different perspectives. The complaint obviously is clear in this corpus, but it is more than anything an exploration of subjectivities, which as a whole diagnose a kind of " the spirit of the times," expressed in sadness, suffering, suffocation, and hopelessness. It is also the management of own recent memory and the only way of expressing the traumatic experience, articulated as a " secret code" that takes shape as artistic pieces.

In his persistent attention to the events of the world, Jaar seeks to be a witness as much as possible rather than an observer. He did it when he made the series about Rwanda, one of his best-known projects, where he spent weeks witnessing the genocide that took place in that African country in 1994.

When the coup d'état was perpetrated, Jaar was 17 years old. In 1974, he began studying architecture and still in shock at what had happened, he began selecting and cutting out photographs from newspapers and magazines. He began to work with these images, focusing on a detail that did not appear in the news, something imperceptible or a fragment that, however, seemed to him revealing in some sense and necessary to be shown. These were the first and decisive exercises that made up his future work methodology, subverting common sense in information, dislocating and, above all, questioning images and the criteria of representation.

Before moving on to the works themselves, it is worth reviewing Jaar's artistic proposal over time, as a corpus that focuses on the very problem of images, a corpus that questions how we see and perceive and how constitutes the distance between what happens in reality and what presented to us as spectators. Alfredo Jaar questions the futility of images when they are decontextualized, and facing this situation, he decides to work with them, helping them communicate, sometimes, if necessary, doing without them. His relationship with representation is raised as a matter of ethics and throughout his work, his concern about how to represent the unrepresentable is expressed.

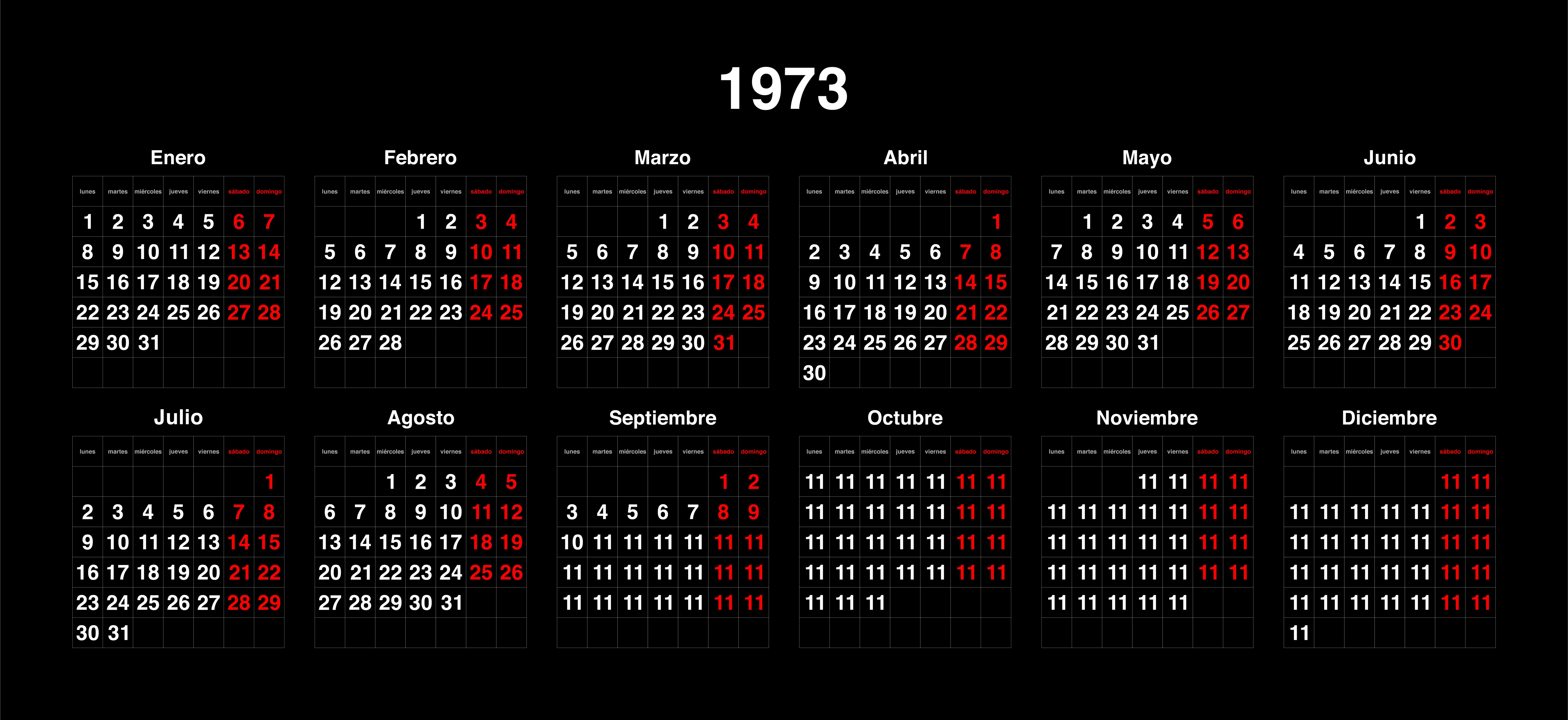

In those years of youth, between blueprints and mockups, Jaar became fascinated with the Letraset template and wanted to create something with it. The date " September 11" naturally came to his mind, and he designed that number in white letters on a black background, followed by the exact time when the first Hawker Hunter plane of the Chilean Air Force attacked the La Moneda palace. That was his first gesture. Jaar then continued to ramble about the tragic date and experimenting with calendars until he stopped at one from 1973, which, upon reaching September 11, no longer reports on the passage of time but remains encapsulated in the dates 11, 11, 11, repeated incessantly. All the calendar data disappeared, and only the sign of the tragedy remained. In recent interviews, Jaar has reflected that after the events of September 11, no one would ever be the same again; We realized with the passage of time and experience that the country as a whole would never be the same again. Also, this incipient work, which dares to alter a social convention as irrefutable as the calendar, leads us to reflect on a critical present established as an extensive present that has not yet been resolved. In the words of philosopher Sergio Rojas: " That tremendous event, that hit us on September 11 is still happening, is not something that is getting further away with each passing day, as if tomorrow it were going to be even further away. On the contrary, we intermittently discover it attached to the present. Even more, with everything that happened all over the world in the 20th century, Rojas argues, the World Wars, the concentration camps, the Gulags, Hiroshima, the Cold War, and the coups d'état, the notion of History did not emerge unscathed and perhaps this partly explains why the world seems to have turned to a dominant contemporaneity."

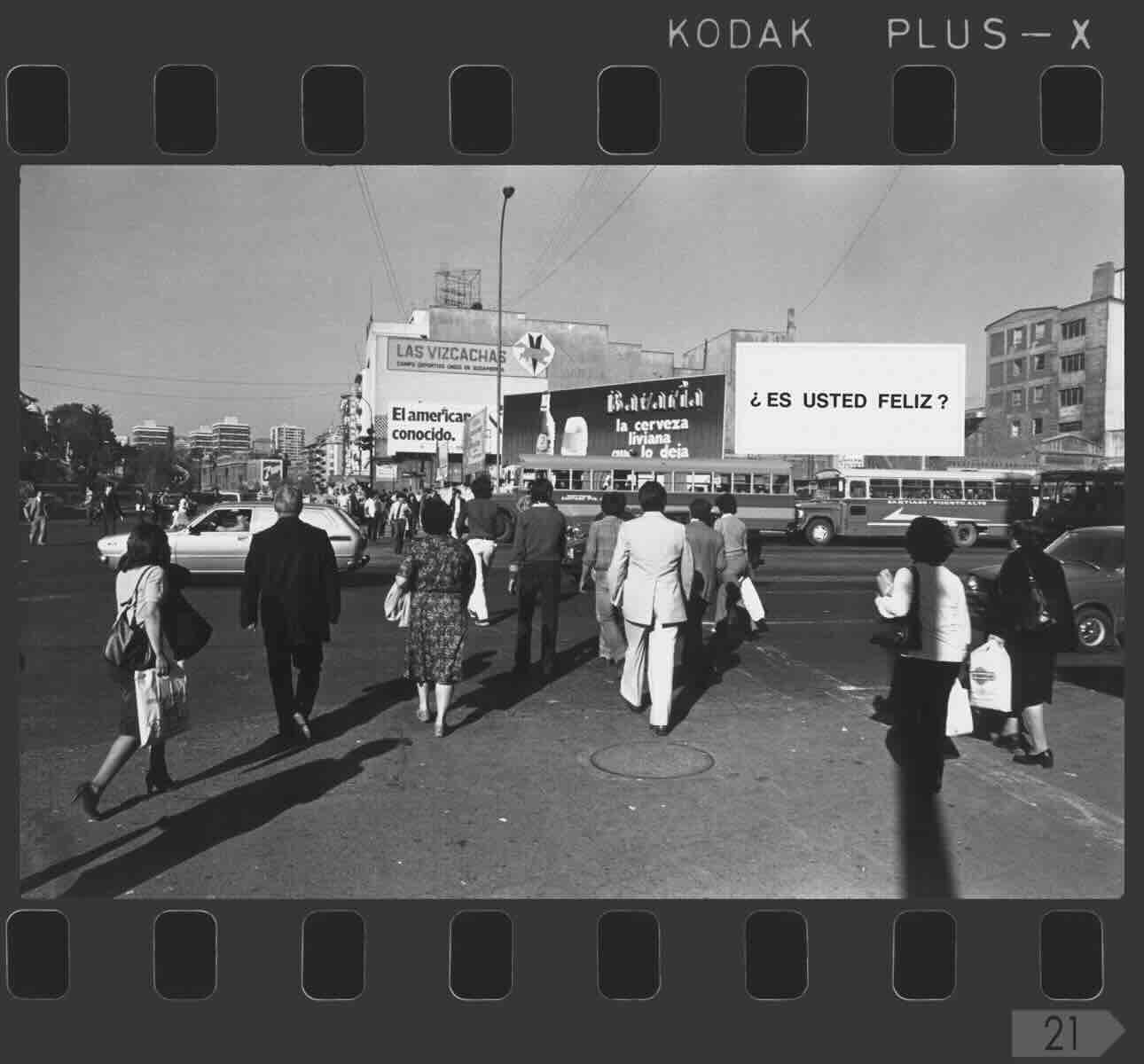

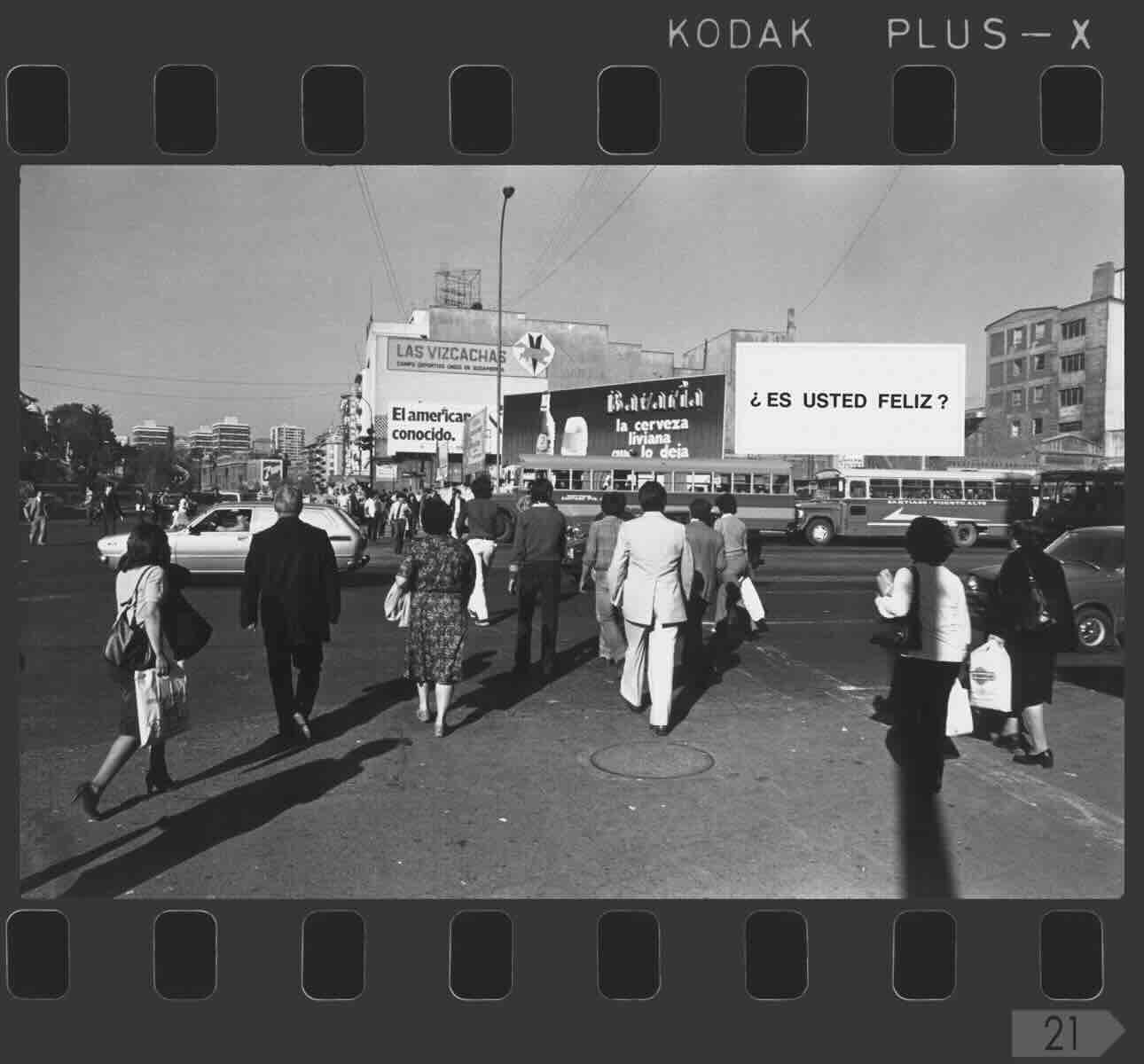

When the problem of Chile occupied the pages of international media and the restless analysis of intellectuals; When solidarity campaigns were being organised in exile, images of the bombing of La Moneda were everywhere and the language of Human Rights was spreading more intensely, Alfredo Jaar, still in Chile, devised his best-known work of that period, Studies on Happiness, a project carried out in seven stages, between 1979 and 1981, the fundamental part of which is the artist's exit onto the streets of Santiago to survey unsuspecting passers-by with the question "Are you happy?" This kind of social diagnosis clearly already showed the innovative position that Alfredo Jaar assumed in dialogue with the social sciences. Using means from sociology, statistics and anthropological approaches that applied codes similar to action research, Jaar managed - in a very surreptitious way, with an innocent question - to scrutinize the mood on the streets of Santiago, even making assessments and giving people the then impossible opportunity to "vote" on the scale of happiness of citizenship during the dictatorship. The quantitative conclusions of this diagnosis were recorded on boards, ironically using classic mint candy balls as a measure of the averages of happiness and unhappiness investigated. In addition to these interventions in public spaces, the entire project is made up of photographs, graphics, videos and group dialogues. Among the recently recovered elements of Studies on Happiness are the audiovisual recordings of the interviews conducted by Jaar at the National Museum of Fine Art, at the Cultural Institut of Las Condes and in his own home. The interviewees, one by one, sat on a podium to answer the central question and elaborate on their state of happiness or unhappiness; many of them were friends of his and influential persons in the cultural resistance of the time, such as the poet Raúl Zurita, the actor Cristián García Huidobro, the actress Malucha Pinto or the editor and visual artist Mario Fonseca, among others. After leaving the podium, the interviewees engaged in spontaneous conversations, like a focus group, where, without mentioning the dictatorship and amidst long minutes of silence, they spoke of the prevailing fear and self-censorship. Jaar would stop to observe them, noticing their physical signs, their looks, their body postures, signals through which these happy or unhappy people generally reflected an opacity that had taken hold in daily life in the early 1980s. Jaar recorded these facial expressions in photographs and video, revealing a common denominator tending toward sad emotions and introspection. Based on this research, he created visual and audiovisual pieces that today constitute a document of memory, testifying to the impact of the dictatorship on subjectivities, perception and collective consciousness.

"Alfredo Jaar. The dark side of the moon" (2024), MNBA. Images: Jorge Brantmayer

As a witness to his present, and at the same time as a protagonist, Jaar was able to experience, measure and record this grey circumstance, where an overloaded and overwhelming Present pushed the days of life into a state of endless emergency. As he has admitted in various interviews, Jaar was making his first works of art unwittingly, ascribed to the conceptual movement of the 20th century, a type of art that reflects on itself, its media and its performance in terms of representation and communication reach. But along with the self-observation of his conditions, implied in this case, Jaar explored his present here in the first person, becoming aware of its significance and its impact.

There is a second creative phase, which brings together the largest number of works around the situation that Chile was going through. This was made in New York, by an architect Alfredo Jaar taking his first steps in international contemporary art or what used to be called "First World." Based in one of the most powerful countries on the planet, whose foreign policies had a direct influence on the coup d'état in Chile, Jaar informs himself and becomes aware of this. From this central territory, he develops works/essays that look towards Chile, which clearly show his anti-imperialist position and confirm an ethical-political dimension in his artistic practice. As part of those regular practices, he became obsessed with the figure of the American Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, cutting out hundreds of photographs that showed him on official visits, talking with other officials or greeting different leaders around the world. In each image, Jaar enclosed Kissinger's face in a red circle and began to design different works with all that material, so that the figure of Kissinger forms a whole sub-theme in the selection of works that brings us together. For his exhibition in Berlin, Alfredo Jaar structured new pieces from his very particular “Kissinger Archive” and carried out, as he regularly does, a very specific proposal for the place that had invited him to exhibit: For several weeks, he intervened in German newspapers with small framed sentences, like advertisements, with the message “Arrest Kissinger!”. Each day in a different language, corresponding to the speech of the countries in which Kissinger's political action had altered, violated or damaged their sovereign state.

Living and working in New York, observing Chile and confirming from a distance the terrible consequences of the institutional breakdown, Alfredo Jaar spontaneously and continually produced these works, which were not intended to be exhibited and many of which were stored as essays until they were discovered just over 10 years ago. At this phase, his recent memory operates intensely, as the main source of research and creation. A personal, affective, occasionally irregular memory, referring - nevertheless - to a phenomenon and a breakdown that we share collectively.

As we well know, the future, so elusive in a context of civilizational deterioration, will not be achieved without justice and truth. From the visual arts, Alfredo Jaar – a declared admirer of Antonio Gramsci – maintains with the Italian philosopher that Culture is a place of resistance from which changes can be thought of, and what artists do is perhaps, in the 21st century, the last remnant of humanity.